The Cherokee

lived in harmony with wildlife and nature in the mountains and foothills for

centuries. However, as European traders

and settlers came into the area overhunting for meat, fur and hides led to a

decrease in the number of game animals.

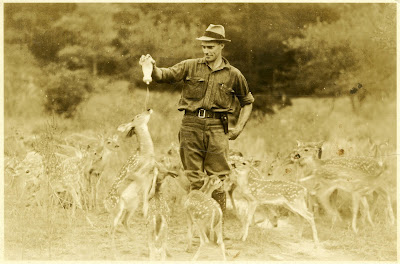

By the early 1900s the white-tail deer population had declined to the point of concern. George Vanderbilt undertook efforts to re-stock deer on his vast estate. Then, following the creation of the Pisgah National Forest, a game preserve was established leading to a rebound in the number of deer in this relatively safe environment.

During the 1930s the herds were large enough that hunting was allowed in some years. Deer were also captured and transported to others areas of North Carolina and surrounding states where white-tail deer had nearly disappeared.

|

| Two small fawns at the Fawn Rearing Station. |

Blankets were used to keep the youngest fawns warm on chilly nights. Precautions were also taken not to frighten them with loud noises, such as automobiles. As the fawns grew they were fed just twice a day, then taught to eat a grain mixture. Finally they were placed in larger fenced areas to graze on their own.

In addition to the fawns, rangers would care for injured adult deer. Both fawns and adult deer were shipped throughout the southeast to increase herds elsewhere.

Data was also collected to study the habits of the white-tail deer and the diseases that affected them. Fredrick J. Ruff’s 1937 study, “The Whitetail Deer of the Pisgah National Game Preserve” remains valuable in deer management today.

Newspaper and magazine articles, as well as news reels shared the story of the Pisgah Fawn Rearing Station across the country making it popular for tourists. Hundreds of visitors received special permission to tour the fawn farm each year.

Budget cuts and the success of repopulating white-tail deer led to the program being phased out in the early 1940s.

|

| Fawns eagerly gather at feeding time. |